SAIDS Explained: Definition, Classes, and Autoimmune Gap

Feb 08, 2026

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases (SAIDS) occupy a defined category within immunology due to specific dysregulation of the innate immune system, resulting in recurrent inflammation that occurs without identifiable external triggers. Unlike autoimmune diseases, SAIDS do not engage the adaptive immune response or produce autoantibodies. This key immunological distinction often leads to misdiagnosis and delayed identification for patients.

Timely recognition remains critical. The average interval from symptom onset to diagnosis can reach 7.3 years, underscoring the need for heightened clinical awareness and improved diagnostic resources. Delineating the differences between SAIDS and autoimmune disorders informs both diagnostic strategies and management approaches. Recent research on CBD products has shown some potential benefits on inflammatory conditions, but the amount of studies and data remains limited and is insufficient to verify efficacy and quality control remains a challenge.

Definition and Characteristics of SAIDS

SAIDS, or Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases, are rare disorders involving excessive, antigen-independent inflammatory responses originating from innate immune system abnormalities. These conditions present as recurrent, systemic inflammation and fever in the absence of high-titer autoantibodies or antigen-specific T-cell involvement.

Immunological Distinctions: Innate Versus Adaptive Immunity

The immune system consists of innate and adaptive branches. This structural difference explains the contrasting clinical and laboratory findings between systemic autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Innate immunity provides immediate, nonspecific defense against threats and activates within 0 to 96 hours of exposure. It includes macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. The innate system detects conserved microbial structures rather than discrete antigens. The innate immune response is rapid but generalized.

Adaptive immunity develops over time, responding specifically to encountered antigens and generating immunological memory. It involves B and T lymphocytes and operates beyond 96 hours post-exposure. This response produces targeted, long-lasting immunity via antibody production and specific cell-mediated reactions.

SAIDS stem from overactivity in the innate immune system, resulting in inflammation without the presence of autoantibodies—a hallmark of autoimmune pathology. SAIDS typically lack serological markers such as antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), which are commonly detected in lupus or rheumatoid arthritis.

Autoimmune diseases result from adaptive immune mechanisms attacking host tissues, often producing autoantibodies and engaging antigen-specific T-cells. Inflammation in autoimmune disorders differs in chronicity and distribution from the episodic or periodic inflammation observed in SAIDS.

SAIDS Classification: Genetic and Mechanistic Variation

Clinicians classify systemic autoinflammatory diseases according to genetic causes and underlying immune mechanisms.

Monogenic SAIDS result from single gene mutations. Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) is the most prevalent monogenic periodic fever syndrome, attributable to mutations in the MEFV gene and observed mainly in Mediterranean populations. FMF is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and characterized by brief fever episodes.

Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes (CAPS) comprise several related conditions caused by NLRP3 gene mutations. CAPS have an estimated prevalence of 2 to 5 per million individuals and commonly present with urticaria-like rash and cold-induced attacks.

Other monogenic SAIDS include TNF Receptor-Associated Periodic Syndrome (TRAPS), with longer fever durations, as well as Hyperimmunoglobulin D Syndrome (HIDS/MKD), typically manifesting early in life.

Polygenic and multifactorial SAIDS involve contributions from multiple genetic loci. These forms are more prevalent outside regions with high FMF frequency and account for a broader spectrum of clinical presentations.

Adult-Onset Still's Disease (AOSD) is a polygenic SAIDS showing HLA gene associations. Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (SJIA) represents the leading rheumatic disease in children. PFAPA (Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, Adenitis) has a documented incidence of approximately 1 in 5,000 children.

Monogenic SAIDS usually present in childhood or infancy, whereas polygenic forms such as AOSD arise in adult populations. Inheritance patterns can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or undefined depending on the specific SAIDS.

Causes of Misunderstanding and Diagnostic Delays

Multiple factors contribute to the frequent under-recognition and misdiagnosis of systemic autoinflammatory diseases.

Clinical symptom overlap introduces diagnostic challenges. Manifestations such as fatigue, joint pain, and rash occur in several diseases and can lead to attribution errors involving infectious or autoimmune causes.

The intermittent presentation of SAIDS symptoms further impedes recognition. Symptoms may flare and remit periodically, in contrast to the typical persistence of autoimmune inflammatory signs and symptoms.

Insufficient clinical familiarity with SAIDS remains a barrier to accurate identification. Appropriate diagnosis and management require specialist knowledge and experience. Patients commonly encounter difficulty accessing clinicians with relevant expertise.

Advances in genetic diagnostics have expanded understanding, yet at least 40 to 60% of cases consistent with SAIDS do not fulfill criteria for specific diagnoses, resulting in the category of undefined SAIDS (uSAIDs). More than 30 genes linked to autoinflammatory disease have been identified since 1997; further research continues to clarify genetic contributions.

Diagnostic Barriers in Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases create diagnostic challenges that extend beyond clinical overlap.

Misclassification as psychiatric disorders is frequently reported. Prominent psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance occur in both autoinflammatory and primary psychiatric disorders. This overlap increases the likelihood of psychiatric misdiagnosis, particularly among women, and contributes to delayed recognition of underlying inflammatory diseases.

Many SAIDS lack specific laboratory biomarkers. Diagnostic accuracy depends on clinical pattern analysis, family history, exclusion of alternative etiologies, and genetic testing where indicated. No single test can definitively confirm the majority of SAIDS.

Consultation with rheumatology or immunology specialists is recommended for complicated cases. Experts review clinical patterns, assess inflammatory markers, conduct genetic testing when available, and systematically differentiate SAIDS from autoimmune or infectious causes.

A thorough, patient, and systematic approach to assessment improves diagnostic reliability. Clinicians document recurring inflammatory episodes, evaluate the absence or presence of known triggers, and record therapeutic responses to guide diagnosis.

Management and Investigation of Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases

Therapeutic options for systemic autoinflammatory diseases have expanded in response to evolving knowledge of inflammatory mechanisms.

IL-1 inhibitors now constitute first-line therapy for many SAIDS. These agents, including anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept, interrupt specific pathways in innate immune activation. Controlled application of these biologics is essential to prevent irreversible organ involvement. Choice of agent and dosing schedule depend on individual pharmacokinetics and disease severity.

Adjunctive therapies include anti-TNF agents for musculoskeletal manifestations, IL-6 inhibitors where indicated, and corticosteroids to manage acute flares. Use of corticosteroids among athletes must be considered in accordance with drug testing regulations as corticosteroids are prohibited on the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Prohibited List. Colchicine remains a standard intervention in FMF to prevent recurrent episodes. Management targets normalization of clinical manifestations and laboratory markers of inflammation through a structured treat-to-target protocol.

Personalization of therapy is required. Treatment adjustments are based on confirmed diagnosis, observed disease activity, and individual tolerance. Regular monitoring of inflammatory parameters enables early detection of complications and timely therapy optimization.

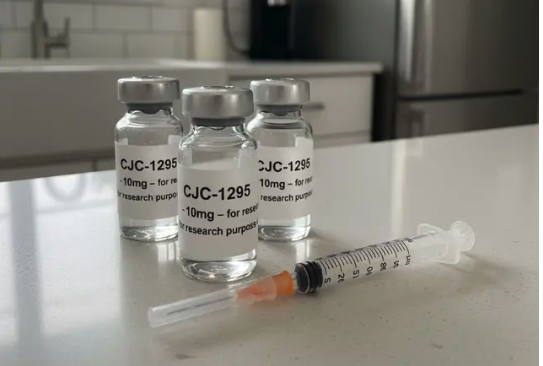

Ancillary health strategies, including attention to general wellness, remain relevant but require consideration of available evidence. Some individuals investigate supplementary substances such as cannabidiol (CBD). Recent studies indicate that CBD may act as a lipid-mediator class-switching agent in innate immune cells, promoting transition from pro-inflammatory to pro-resolving mediators. However, the FDA has not approved CBD for treatment of inflammatory conditions and research remains preliminary. Dietary supplements and CBD products may not be legally marketed as a treatment for inflammation or diseases like SAIDS but further research may further support its benefits in that regard.

Ensuring supplement purity is essential if the intended benefits are going to be effective. Third-party certification programs verify CBD content, check for THC limits, and and screen for contaminants. Comprehensive analytical testing panels in the Certified CBD program assess for over 450 drugs, banned substances, heavy metals, pesticides, and microbiological agents. This type of quality control verification goes above and beyond industry standards and enhances transparency while evidence continues to emerge regarding efficacy and safety.

FAQ About SAIDS

Definition of SAIDS

SAIDS refers to Systemic Autoinflammatory Diseases, encompassing rare disorders of innate immune dysregulation characterized by recurrent systemic inflammation.

Distinction from Autoimmune Diseases

SAIDS involve innate immune mechanisms without autoantibody formation, whereas autoimmune diseases result from adaptive immune system errors, including autoantibody production and tissue attack.

Etiological Background

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases arise due to abnormal activation of innate immune pathways. Etiology may include single-gene (monogenic), multiple-gene (polygenic), or as yet undefined genetic influences.

Genetic Factors

Genetic contributions are common in SAIDS. Monogenic forms result from discrete mutations, while polygenic forms involve complex genetics. Some patients lack detectable genetic alterations.

Prevalence

Epidemiologic rates range from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 1,000,000 persons, depending on SAIDS subtype and population.

Key Differences from Autoimmunity

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases exhibit episodic, innate-driven inflammation and absence of autoantibodies, while autoimmune diseases are marked by chronic adaptive immune responses and antibody or T-cell specificity.

History of Identification

"Autoinflammation" terminology was proposed in 1999. The earliest documented description of FMF dates to 1949, and the first gene (MEFV) was identified in 1997.

Summary

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases define a set of immune system disorders with distinct innate immune system pathogenesis, clinical features, and genetic factors. Identification of these conditions as separate from autoimmune processes improves accuracy in diagnosis and therapy selection.

Ongoing research continues to identify genetic variants and supports development of pathway-targeted treatments. Since the late 1990s, over 30 relevant genes have been identified, yet many cases still lack definitive molecular explanation.

Specialized clinical expertise is necessary for accurate evaluation and management. The complexity and phenotypic overlap of SAIDS with other inflammatory disorders necessitate comprehensive assessment by clinicians with domain-specific training.

Consideration of CBD supplements in inflammation management should be guided by evidence and regulatory standards. While some scientific evidence is available studies to date have been limited and conclusions are not definitive. Product quality and contaminant screening by third-party certification programs provides objective assurance of manufacturing, labeling and product contents, which is especially important for consumers and in areas where clinical research is ongoing and regulatory approval is pending.

.png)